Quadruped Path Planner for Dynamic Environments

September 2024 - November 2024

- Tech Stack: C++, ROS, Git, Gazebo

- Summary

Demonstrated a global path planner for a quadruped robot using C++ and ROS, that accounts for dynamic obstacles and the z-height of the robot.

Executed a Lazy-PRM with D* Lite planner with kinodynamic constraints and state space comprising x, y, z, yaw, and velocity components.

Achieved a success rate of 93%.

My role: Implemented the z-height controller, and helped implement Lazy PRM-D* Lite.

- In-Depth

Introduction

This project was completed as part of the Planning and Decision-making in Robotics (16-782) course at CMU. The aim of this project was to implement a Lazy PRM-D* Lite global path planner. Experimental validation showed that our planner achieved a 95% success rate.

Fig-1 Project Spirit Quadruped Robot Motivation

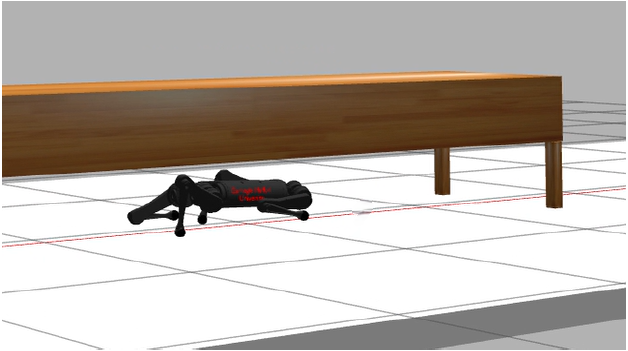

The motivation was to develop a planner that can work in dynamic environments, by replanning quickly while also generating optimal paths. Furthermore, we needed the planner to also consider the z-height of the robot, so that it could, for example, go under a table or over a bed. To address these objectives, we implemented Lazy PRM-D* while considering z as part of the state.Lazy PRM with D* and Kinodynamic constraints

The state vector of the planner is <x, y, z, vx, vy, vz>. This section will give a brief overview of our planner.PRM Overview

The PRM (Probabilistic Roadmap) serves as a representation of feasible motion paths through the environment. With a generated map and a given start and goal state, a search-based planner like A* can be used in conjunction to retrieve a path, if it exists. However, the PRM generation process is computationally expensive and hence performed offline. The advantage lies in the fact that once generated, the graph can be used to find paths to any combination of start and goal states. Typically, while generating the PRM, sampled nodes that lie in obstacles are rejected, ensuring that the graph represents only collision-free paths. However, this approach is only effective in static environments, as any changes in the environment will necessitate regeneration of the PRM.To address this limitation, a modification to PRM for dynamic environments is called Lazy PRM. Unlike traditional PRM, this approach does not reject nodes that lie within obstacles. Instead, it retains them in the graph, but with an infinite cost. This modification ensures that the roadmap remains valid even if the environment changes. When an obstacle moves or disappears, the cost of the corresponding nodes can be dynamically updated rather than requiring a complete regeneration of the graph. This small modification enables PRMs to be used in dynamic environments.

A* Search Overview

The cost updation and re-planning is handled by the A* search, or for a faster and more optimal re-planning algorithm, D* Lite. D* Lite is a modification of A* that reuses and leverages information gained during previous searches, hence making the search faster, as replanning is not done from scratch, unlike in A*. Furthermore, since it is essentially A*, the path obtained is optimal, for a given the map. As long as we can create a very dense PRM, which is feasible since it's done offline, A* can find the most optimal path. If speed is a priority, weighted-A* can be used instead.

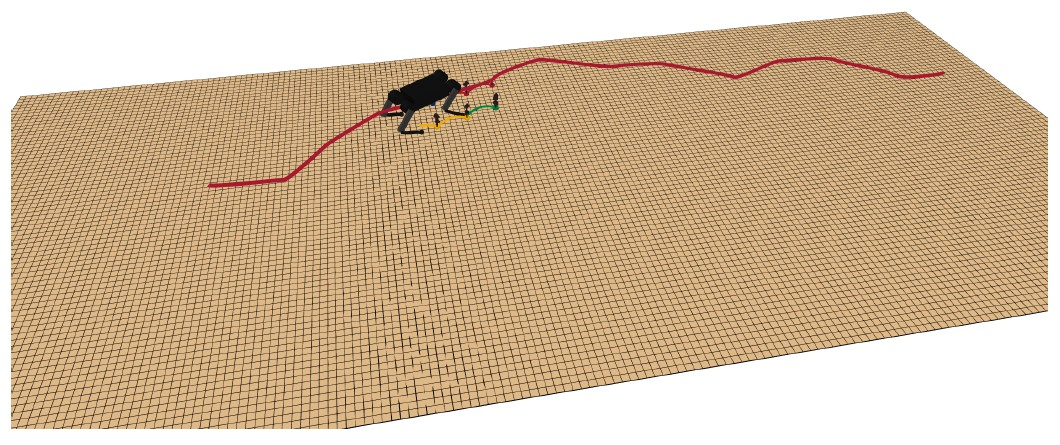

Fig-2 Visualization of the path generated by the planner Kinodynamic Constraints

Additionally, the planner incorporates kinodynamic constraints into its re-planning framework. These constraints ensure that the transitions between states adhere to the physical and dynamic limitations of the system. Metrics such as stance time, accelerations, and ground reaction forces (GRFs) are calculated to validate the feasibility of motion between states. This integration guarantees that the paths generated during re-planning are not only efficient but also physically realizable, which is critical for applications such as quadruped locomotion or other systems requiring adherence to dynamic constraints.Planning in z

One of the main objectives was to add a third dimension, z (height), to the planner to enable height-aware navigation. However, instead of directly sampling z, which would significantly increase the state space size and planning complexity, a 'lazy' approach has been implemented to improve the planning speed. The way this is done is by first checking if the nominal z of the robot collides with obstacles for a given x and y location. If it clears the obstacle check, that is, no collision is detected, z is left unchanged. However, if it collides, the minimum z (the lowest height at which the robot can successfully walk) is checked against the obstacle. If it passes the check, the robot height is set to z minimum, effectively allowing crouching. But if even that fails, it means that the state is invalid, as the robot cannot fit through it despite crouching.

Fig-3 Traversing under a table: Planning in z-dimension

- Results

Our planner achieved a success rate of 93% in the test environment, proving its effectiveness.